The War Years 1914 - 1919

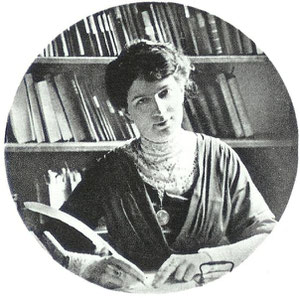

When the war came in August, Teilhard returned to Paris to help Boule store museum pieces, to assist cousin Marguerite turn the girl's school she headed into a hospital, and to prepare for his own eventual induction.

August was a disastrous month for the French army; the German forces executed the Schlieffen Plan so successfully that by the end of the month they were about thirty miles from Paris. In September

the French rallied at the Marne and Parisians breathed easier.

Because Teilhard's induction was delayed, Teilhard's Jesuit Superiors decided to send him back to Hastings for his tertianship, the year before final vows. Two months later word came that his younger

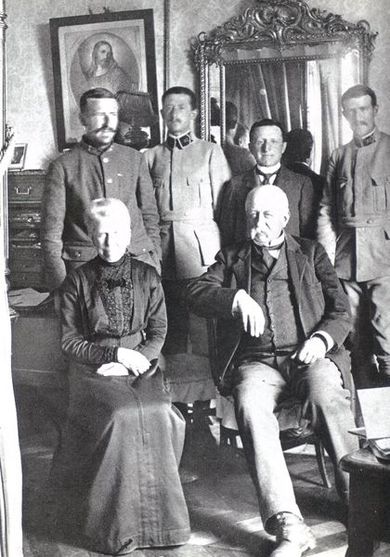

brother Gonzague had been killed in battle near Soissons. Shortly after this Teilhard received orders to report for duty in a newly forming regiment from Auvergne. After visiting his parents and his

invalid sister Guiguite at Sarcenat, he began his assignment as a stretcher bearer with the North African Zouaves in January 1915. At his request he was sent to the front and also

became chaplain.

The powerful impact of the war on Teilhard is recorded in his letters to his cousin, Marguerite, now collected in The Making of a Mind. They give us an intimate picture of Teilhard's initial enthusiasm as a "soldier-priest," his humility in bearing a stretcher while others bore arms, his exhaustion after the brutal battles at Ypres and Verdun, his heroism in rescuing his comrades of the Fourth Mixed Regiment, and his unfolding mystical vision centered on seeing the world evolve even in the midst of war. In these letters are many of the seminal ideas that Teilhard would develop in his later years. For example during a break in the fierce fighting at the battle of Verdun in 1916 Teilhard wrote the following to his cousin, Marguerite:

"I don't know what sort of monument the country will later put up on Froideterre hill to commemorate the great battle. There's only one that would be appropriate: a great figure of Christ. Only the image of the crucified can sum up, express and relieve all the horror, and beauty, all the hope and deep mystery in such an avalanche of conflict and sorrows. As I looked at this scene of bitter toil, I felt completely overcome by the thought that I had the honour of standing at one of the two or three spots on which, at this very moment, the whole life of the universe surges and ebbs places of pain but it is there that a great future (this I believe more and more) is taking shape." (The Making of a Mind, New York, 1965, pp. 119/20.)

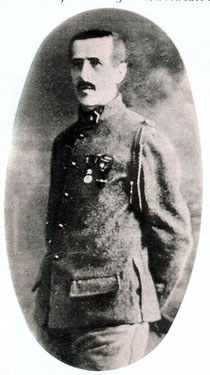

Through these nearly four years of bloody trench fighting Teilhard's regiment fought in some of the most brutal battles at the Marne and Epres in 1915, Nieuport in 1916, Verdun in 1917 and Chateau Thierry in 1918. For his bravery Teilhard was awarded the Medaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre. Teilhard was much admired by the men of his unit for his friendship, courage, and gallantry. He soon became known as a man who could be relied on in a difficult or dangerous situation. Persuaded that death was only a change of state he would go out under a hail of bullets and calmly bring back the dead and wounded. Teilhard was active in every engagement of the regiment for which he was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur in 1921.

Throughout his correspondence he wrote that despite this turmoil he felt there was a purpose and a direction to life more hidden and mysterious than history generally reveals to us. This larger meaning, Teilhard discovered, was often revealed in the heat of battle. In one of several articles written during the war, Pierre expressed the paradoxical wish experienced by soldiers-on-leave for the tension of the front lines. He indicated this article in one of his letters saying:

"I'm still in the same quiet billets. Our future continues to be pretty vague, both as to when and what it will be. What the future imposes on our present existence is not exactly a feeling of depression; it's rather a sort of seriousness, of detachment, of a broadening, too, of outlook.

This feeling, of course, borders on a sort of sadness (the sadness that accompanies every fundamental change); but it leads also to a sort of higher joy . . . I'd call it `Nostalgia for the Front'. The reasons, I believe, come down to this; the front cannot but attract us because it is, in one way, the extreme boundary between what one is already aware of, and what is still in process of formation. Not only does one see there things that you experience nowhere else, but one also sees emerge from within one an underlying stream of clarity, energy, and freedom that is to be found hardly anywhere else in ordinary life - and the new form that the soul then takes on is that of the individual living the quasi-collective life of all men, fulfilling a function far higher than that of the individual, and becoming fully conscious of this new state. It goes without saying that at the front you no longer look on things in the same way as you do in the rear; if you did, the sights you see and the life you lead would be more than you could bear. This exaltation is accompanied by a certain pain. Nevertheless it is indeed an exaltation. And that's why one likes the front in spite of everything, and misses it." (The Making of a Mind, p. 205.)

Teilhard's powers of articulation are evident in these lines. Moreover, his efforts to express his growing vision of life during the occasional furloughs also brought him a foretaste of the later ecclesiastical reception of his work. For although Teilhard was given permission to take final vows in the Society of Jesus in May 1918, his writings from the battlefield puzzled his Jesuit Superiors especially his rethinking of such topics as evolution and original sin.

He was convinced that if he had indeed seen something, as he felt he had, then that seeing would shine forth despite obstacles. As he says in a letter of 1919, "What makes me easier in my mind at

this juncture, is that the rather hazardous schematic points in my teaching are in fact of only secondary importance to me. It's not nearly so much ideas that I want to propagate as a spirit: and a

spirit can animate all external presentations" (The Making of a Mind, p. 281).

After his demobilization on March 10, 1919, Teilhard returned to Jersey for a recuperative period and preparatory studies for concluding his doctoral degree in geology at the Sorbonne, for the Jesuit provincial of Lyon had given his permission for Teilhard to continue his studies in natural science. During this period at Jersey Teilhard wrote his profoundly prayerful piece on "The Spiritual Power of Matter."

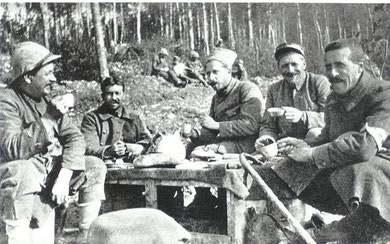

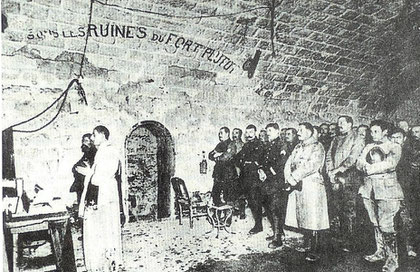

This is though to be Teilhard offering Mass before the Battle of Douaumont, October 1916. He was the only priest in the area at that time.

Praise for the Americans

From a letter to his cousin, Marguerite, July 25, 1918

We had the Americans as neighbors and I had a close-up view of them. Everyone says the same: they're first-rate troops, fighting with intense individual passion concentrated on the enemy and wonderful courage. The only complaint one would make about them is that they don't take sufficient care; they're too apt to get themselves killed. When they are wounded they make their way back holding themselves upright, almost stiff, impassive, and uncomplaining. I don't think I have ever seen such pride and dignity in suffering...... That week was a revelation to our men of what these allies mean to them.

Teilhard de Chardin

Teilhard de Chardin