Years of Research, Travel and Teaching - 1920-1927

After returning to Paris, Teilhard continued his studies with Marcellin Boule in the phosphorite fossils of the Lower Eocene period in France. Extensive field trips took him to Belgium where he also began to address student clubs on the significance of evolution in relation to current French theology. By the fall of 1920, Teilhard had secured a post in geology at the Institute Catholique and was lecturing to student audiences who knew him as an active promoter of evolutionary thought. In 1922 Teilhard received a Doctorate with Distinction and was elected president of the Geological Society of France. Teilhard was now recognized as a master in his field and was consulted by his peers.

The conservative reaction in the Catholic Church initiated by the Curia of Pius X had abated at his death in 1914. But the new Pope, Benedict XV renewed the attack on evolution, on "new theology," and on a broad spectrum of perceived errors considered threatening by the Vatican Curia. The climate in ecclesiastical circles towards the type of work that Teilhard was doing gradually convinced him field work in geology paleontology would not only help his career but would also quiet the controversy in which he and other French thinkers were involved. The opportunity for field work in China had been open to Teilhard as early as 1919 by an invitation from the Jesuit scientist Emile Licent who had undertaken paleontological work in the environs of Peking. On April 1, 1923, Teilhard set sail from Marseille bound for China. Little did he know that this "short trip" would initiate the many years of travel to follow.

The Years of Travel

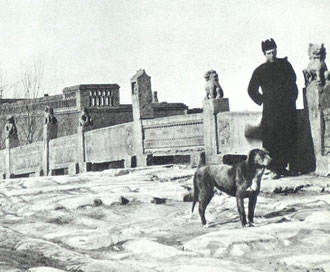

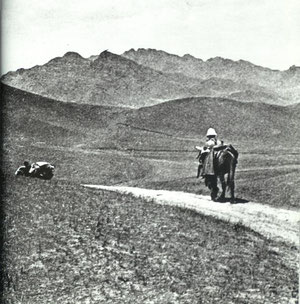

Teilhard's first period in China was spent in Tientsin, a coastal city some eighty miles from Peking where Emile Licent had built his museum and housed the fossils he had collected in China since his arrival in 1914. The two French Jesuits were a contrast in types. Licent, a northerner, was unconventional in dress, taciturn and very independent in his work. He was primarily interested in collecting fossils rather than interpreting their significance. Teilhard, on the other hand, was more urbane; he enjoyed conversational society in which he could relate his geological knowledge to a wider scientific and interpretive sphere. Almost immediately after his arrival Teilhard made himself familiar with Licent's collection and, at the latter's urging, gave a report to the Geological Society of China. In June 1923 Teilhard and Licent undertook an expedition into the Ordos desert west of Peking near the border with Inner Mongolia. This expedition, and successive ones during the 1920s with Emile Licent, gave Teilhard invaluable information on Paleolithic remains in China. Teilhard's correspondence during this period gives penetrating observations on Mongolian peoples, landscapes, vegetation, and animals of the region.

Teilhard in India, 1924

Teilhard's major interest during these years of travel was primarily in the natural terrain. Although he interacted with innumerable ethnic groups he rarely entered into their cultures more than was necessary for expediting his business or satisfying a general interest. One of the ironies of his career is that the Confucian tradition and its concern for realization of the cosmic identity of heaven, earth and man remained outside of 'Teilhard's concerns. Similarly tribal peoples and their earth-centered spirituality were regarded by Teilhard as simply an earlier stage in the evolutionary development of the Christian revelation. Teilhard returned to Paris in September 1924 and resumed teaching at the Institute Catholique. But the intellectual climate in European Catholicism had not changed significantly. Pius XI, the new Pope since 1922, had allowed free reign to the conservative factions. It was in this hostile climate that a copy of a paper that Teilhard had delivered in Belgium made its way to Rome. A month after he returned from China Teilhard was ordered to appear before his provincial Superior to sign a statement repudiating his ideas on original sin. Teilhard's old friend Auguste Valensin was teaching theology in Lyon, and Teilhard sought his counsel regarding the statement of repudiation. In a meeting of the three Jesuits, the Superior agreed to send to Rome a revised version of Teilhard's earlier paper and his response to the statement of repudiation.

In the interim before receiving Rome's reply to his revisions, Teilhard continued his classes at the Institute. Those students who recalled the classes remembered the dynamic quality with which the young professor delivered his penetrating analysis of homo faber. According to Teilhard the human as tool-maker and user of fire represents a significant moment in the development of human consciousness or hominization of the species. It is in this period that Teilhard began to use the term of Edward Suess, "biosphere," or earth-layer of living things, in his geological schema. Teilhard then expanded the concept to include the earth-layer of thinking beings which he called the "noosphere" from the Greek word nous meaning "mind." While his lectures were filled to capacity, his influence had so disturbed a bloc of conservative French bishops that they reported him to Vatican officials who in turn put pressure on the Jesuits to silence him.

The Jesuit Superior General of this period was Vladimir Ledochowski, a former Austrian military officer who sided openly with the conservative faction in the Vatican. Thus in 1925 Teilhard was again ordered to sign a statement repudiating his controversial theories and to remove himself from France after the semester's courses.

Teilhard's associates at the museum, Marcellin Boule and Abbe Breuil, recommended that he leave the Jesuits and become a diocesan priest. His friend, Auguste Valensin, and others recommended signing the statement and interpreting that act as a gesture of fidelity to the Jesuit Order rather than one of intellectual assent to the Curia's demands. Valensin argued that the correctness of Teilhard's spirit was ultimately Heaven's business. After a week's retreat and reflection on the Ignatian Exercises, Teilhard signed the document in July 1925. It was the same week as the Scopes "Monkey Trial" in Tennessee which contested the validity of evolution.

In the spring of the following year Teilhard boarded a steamship bound for the Far East. The second period in Tientsin with Licent is marked by a number of significant developments. First, the visits of the Crown Prince and Princess of Sweden and later that of Alfred Lacroix from the Paris Museum of Natural History, gave Teilhard new status in Peking and marked his gradual movement from Tientsin into the more sophisticated scientific circles of Peking. Here American, Swedish, and British teams had begun work at a rich site called Chou-kou-tien. Teilhard joined their work contributing his knowledge of Chinese geological formations and tool-making activities among prehistoric humans in China. With Licent Teilhard also undertook a significant expedition north of Peking to DalaiNor. Finally, in an effort to state his views in a manner acceptable to his superiors Teilhard wrote The Divine Milieu. This mystical treatise was dedicated to those who love the world; it articulated his vision of the human as "matter at its most incendiary stage."

Meanwhile Teilhard had been in correspondence with his superiors who finally allowed him to return to France in August 1927.

Teilhard de Chardin

Teilhard de Chardin